Research Questions/Objectives:

How can we use High Resolution Satellite Imagery for Small Waterbodies in West Queensland to better inform us of their supply, with no ongoing gauging station data?

In this project, we aim to expand our limited understanding of water dynamics in West Queensland to improve mapping data, while also advising grazing and land management practices and strategies for livestock to the agricultural sector. We seek to do this through utilisation of High-Resolution Satellite Imagery to define small waterbodies, their availability to cattle, walking distances and to generally increase farmers, and alike, knowledge of their supply.

Brief Description of the Project:

Due to climate variability with the onset of climate change, and passing the 1.5 degree threshold, it is becoming increasingly difficult to predict climate variability in areas with little water dynamic data. This includes West Queensland, creating uncertainty in the cattle industry and other agricultural practices. Water is an imperative resource to any living being, other than it being a resource to humans and our farming practices, it is imperative for all healthy life on Earth. Currently, cattle are traversing long distances in search for waterbodies, causing loss of cattle in extreme cases, increasing costs and supplies long term. Utilising high resolution satellite imagery to measure water supply in catchments where there are insufficient ground-based monitoring, aids in the interpretation of water body dynamics and availability with the increase in climate variability, increasing local knowledge for farmers and alike. By using these findings, we can create ways to enhance the supply of water to farmers and their cattle, without the need for either to traverse long distances. Perusing scientific literature to gain an understanding of the methodology for satellite data resulted in choosing both optical and radar imagery through Landsat, Sentinel-one/two and Radarsat. Qualities of use determined were permeability of cloud cover during flooding events, deciphering between shallow and deep water bodies, vegetation covering smaller waterbodies and optimal viewing conditions. Analysis of imagery will be through ArcGIS, allowing for areas of most and least concern to be identified following further research through drone mapping of high concern areas to verify satellite imagery.

Background and Significance of the Research Question to drought risk, vulnerability, preparedness, or resilience:

This project can be utilised by many farmers, and alike, in West Queensland (WQLD) to better inform themselves on information used for grazing and cattle management. To date, there is very limited data available on past water body dynamics for the general public in WQLD which has resulted in loss of livestock through drought, lack of concise weather predictions and lack of interest from the scientific community. Farmers and alike will be able to use the data provided at the end of this project to better inform themselves on the planets changing climate patterns in their area. With the onset of climate change looming over humanity, it is beginning to change how we predict the future. In savanna systems in WQLD, where in the past there has been little attention given to our livestock and farmland, we now have the opportunity to change this and delve deeper into the systems at play in disequilibrium savanna areas through high resolution satellite imagery. By combining data from Landsat, Sentinel One and Sentinel Two, we will be able to have a comprehensive overview of small water bodies in these areas and can change the way water is delivered to livestock and maintain better grazing practises and the habitability of our Australian outback.

Academic and research experience relevant to the honours project:

At this stage I no academic or research experience other than just graduating a Bachelor of Environmental Practice at James Cook University in March, 2024.

Principal Supervisor’s skills and experience in relation to this project topic:

Ben Jarihani is a Hydrologist who has completed a considerable amount of research to do with Irrigation and Drainage Engineering, Water Resources Engineering, Hydraulic Design, Geomorphology, Soil Erosion, and Wetland Modeling over the last two decades. He has spoken at conferences at the university of Central Asia, holds an Adjunct Senior Research Scientist position at the University of the Sunshine Coast, Australia and is currently a senior Data scientist at James Cook University. He has completed many projects utilising both High-Resolution Satellite Imagery and Lidar technologies.

When I was around 10 years old, I joined my local Scouting movement and attended the weekly scout night with many other kids my age. Soon after, I went on a couple of hikes and camping trips with the regional and local scout groups. It wasn’t until I went on a particular hike through Hidden Valley that I was completely awe-struck by the view that lay before me. At this point in my life, I had never seen anything so beautiful and felt so connected to the surrounding, pristine environment. It was in this very moment that I knew I had to do something in the future to ensure I could savor the same feeling again.

This major turning point in my life drove me to try my best in the rest of my secondary schooling to ensure I could pursue an environmental science degree. Through my bachelor, I explored many different areas of environmental science to see what the world had to offer. Now, after graduating in 2024, I am so thankful that I listened to my younger self and tried as many subjects as possible, even when the going got tough. Now, I am pursuing my honours, a research project in small water body dynamics and am beginning to realise that environmental science has so much more to offer than what I once thought. I am completely enamoured by water and what it has brought to this planet, I want to discover what amazing things it will do next. For this reasoning, I am pursuing a career as a research Geomorphologist and am hoping to discover what landforms can be carved into the landscape over my career.

Future Career Goals:

My vision for the future is to be a research scientist in any way, shape or form. I have the main goal of becoming a Geomorphologist specialising in Fluvial/Glacial systems and major flooding events throughout Earths’ history. A particular time of interest is the Younger Dryas epoch, as it would be a dream to study such a large-scale event. My near future career goals consist of attending as many networking events, seminars, online lecture series and field work opportunities as possible to set myself up for the future. The overarching theme I have learnt from my studies so far is – even though there may be many disciplines in the environmental science world, water overlaps into many different fields. While hydrology is studied, it still resides within the whole system and dynamically works within the system, either positively, negatively or enabling an equilibrium, creating balance. Water is responsible for life, creation or destruction of landscapes and the evolution of them. Other fields to do with water include aquaculture, oceanography, marine science, marine biology, ecosystem biodiversity and many others, which just goes to show how special it is. We still have much to learn, and I feel as though humanity has begun to take its first big steps in discovering the mysteries of water on this planet, from discovering oxygen in the deep ocean to finding it in the mantle.

Key Research Findings Summary Report:

Mapping small water body dynamics in North-West Queensland using high-resolution satellite imagery

By Keleisha Moore

Supervisors: Dr Ben Jarihani, Dr Jack Koci and Dr Helen McCoy-West

Overview:

The accelerating impacts of climate change are intensifying the hydrological cycle, driving increased demand for high-resolution satellite imagery (HRSI) in water-based applications. While these tools are commonly employed for managing large-scale water bodies such as reservoirs, dams, and anthropogenic river systems, small water bodies (SWBs) in semi-arid rangelands are often overlooked despite their critical ecological importance. This project aims to utilize high-resolution satellite imagery to map and monitor small water bodies and farm dams to improve grazing land management. Each month, images will be analysed from satellite products to assess the shrinkage or expansion of water bodies (Surface Area) and determine their precise locations. The focus is on understanding the availability and dynamics of these water resources, which are vital for livestock, domestic use and wildlife habitats.

Aims:

Objective one: Investigate accuracy of differing resolution satellite products for mapping small water bodies.

Objective two: Investigate temporal dynamics in water extent and area for selected water body products.

Methods:

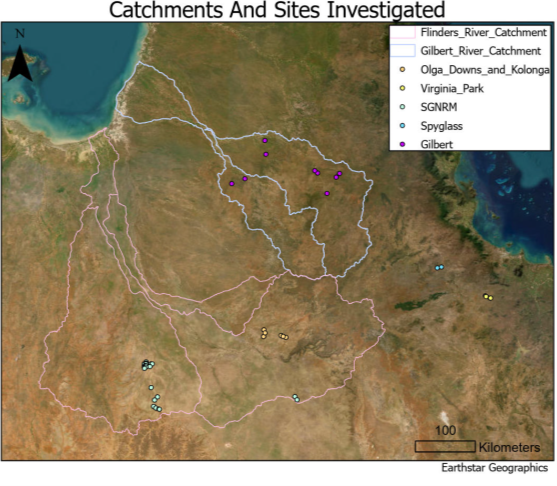

This study investigates the accuracy of both optical and radar satellite imagery in extracting surface water area for SWBs with a minimum size of 10 m². Using the Flinders and Gilbert catchments in Queensland as a case study (figure 1), Landsat (30 m pixel), Sentinel-2 (10 m pixel) and Planet Explorer (3 m pixel) imagery will be overlaid and compared to assess total area coverage and the number of detected water bodies for catchment scale monthly dynamics. At a finer scale, all three products will be analysed across 49 sites (figure 1) monthly throughout 2024 to capture dynamic shrink-swell patterns of SWBs. These sites include ephemeral water bodies in an anastomosing river system, farm dams, and abandoned mine pits, selected based on diverse geometry, depth, bathymetry, and vegetation characteristics. For ground-truthing, drone-captured imagery with a resolution of 2 cm per pixel were used at selected sites to validate surface water area estimations.

Results:

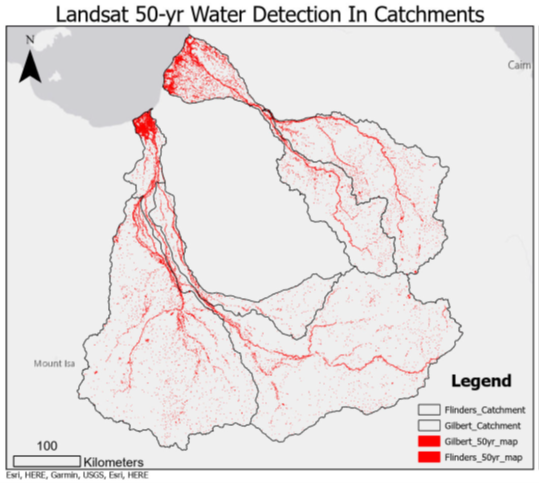

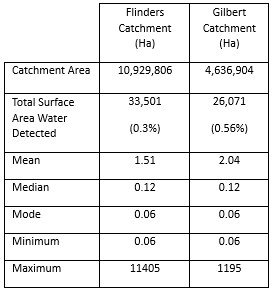

Catchment scale analysis in figure 2 shows that Landsat is unable to detect SWB below 0.06ha (60m2) throughout the last 50 years of available detection due to its low resolution. The median, mode and minimum all point to a dataset skewed towards Very Small Waterbodies within both catchments. Due to this, Sentinel-2 was chosen for comparison of the catchment scale monthly analysis for 2024 to determine quantity of small waterbodies missed between differing resolutions of satellite imagery.

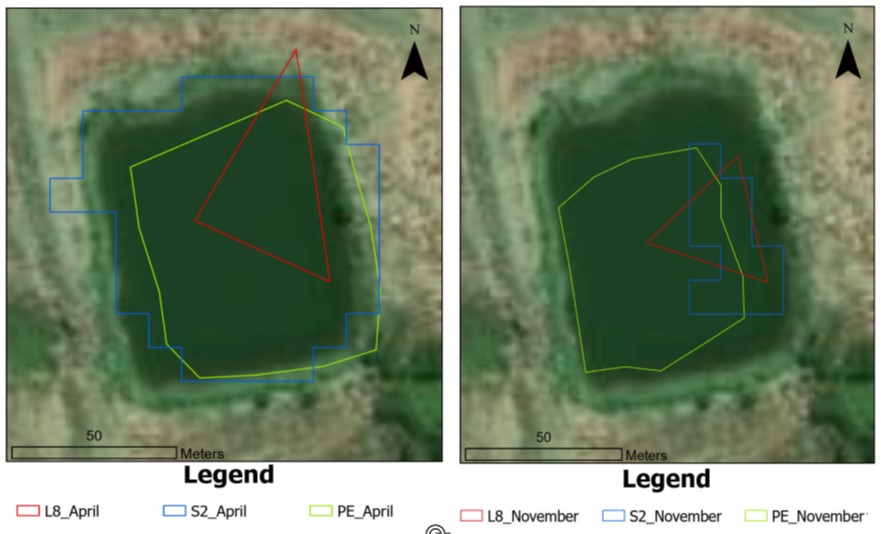

At the individual scale, anthropogenic farm dams (amongst other complicated geometry waterbodies) were selected due to their simple geometry for satellite detection. In figure 3, the varying detection capabilities between Landsat, Sentinel-2 and PlanetExplorer are seen through the products differing resolutions. It can be stated that Planet satellites had the most accurate detection of water between the wet and dry seasons as the geometry of detection best matches the shoreline of the water body. Sentinel-2 detected full surface area of water extent in wet season but struggled in the dry season. Finally, Landsat did detect water in wet and dry seasons but failed to quantitatively show an accurate depiction of surface area water extent.

Conclusion:

Finalised results will provide a detailed linkage between small- and large-scale hydrological systems, showcasing the utility of HRSI for managing ecologically significant SWBs in semi-arid rangeland environments. The presence of vegetation (e.g. dense riparian cover and aquatic or floating vegetation) further complicates classification. These features can obscure water surfaces or alter reflectance signatures, leading to underestimation of actual water extent. Additionally, the shape and geometry of water bodies also influence detection. This comprehensive approach will advance the role of HRSI in addressing water resource challenges exacerbated by climate variability.

Executive Summary: Practical Applications

Mapping small water body dynamics in North-West Queensland using high-resolution satellite imagery

By Keleisha Moore

Supervisors: Dr Ben Jarihani, Dr Jack Koci and Dr Helen McCoy-West

Effective water management is a growing priority in semi-arid regions like North-West Queensland, especially in the face of increasing climate variability and prolonged droughts. Small water bodies (SWBs), such as farm dams, wetlands, and natural waterholes, play a vital role in supporting agriculture, biodiversity, and landscape resilience.

This study assessed the performance of three differing resolution satellite systems (PlanetScope, Sentinel-2, and Landsat) in detecting and monitoring small water bodies across the region. The goal was to explore how satellite imagery can assist landholders and regional managers in better understanding water availability, planning infrastructure, and supporting environmental monitoring.

The following applications were determined:

1. Monitoring Water Supply for Graziers

Satellite imagery clearly captured seasonal cycles of wet and dry conditions, with water bodies expanding after rainfall and shrinking during dry periods. These patterns can help graziers monitor farm dam levels remotely, assess water distribution across large properties, and plan for strategic water use. By linking surface area estimates from satellites with digital elevation models (DEMs), it’s also possible to calculate dam’s volume, offering a more complete picture of available water. This has practical applications for automating pump systems, planning livestock movements, and managing water more efficiently across large-scale grazing operations.

2. Planning Farm Infrastructure and Grazing Strategies

Satellite analysis can also track livestock movement patterns in relation to water access. By identifying how far cattle are walking to reach water, especially on hotter and drier days, graziers can make evidence-based decisions on where to place new farm dams, shade structures, or vegetation corridors. These decisions help reduce animal fatigue, improve productivity, and protect pasture biodiversity and ecosystem health. Over time, this approach contributes to climate-smart grazing systems that support both animal welfare and land condition.

3. Ecological Monitoring and Biodiversity Protection

Small water bodies are hotspots of biodiversity, especially in arid and semi-arid landscapes where they serve as refuges for wildlife, including invertebrates, birds, and mammals. Satellite imagery allows researchers and land managers to map and track these sensitive ecological zones, identifying areas that may be at risk due to drying, erosion, or land use change. This data can inform conservation strategies, set baseline conditions, and guide restoration efforts, helping ensure that critical ecosystems continue to support biodiversity in a changing climate.

Choosing the Right Satellite for the Task

Each satellite system offers different strengths and trade-offs:

PlanetScope provides finer detail with its commercially licensed, downloadable imagery for use in running agricultural irrigation pumps or conducting biodiversity assessment. However, viewing PlanetScope’s imagery online is free for viewing dam levels, water distribution in farms across semi-arid zones and planning infrastructure and strategic water use. In contrast, Sentinel and Landsat have coarser resolution but are free to view and download for all applications. These products are widely used for broader-scale regional analysis and together, they offer a flexible and scalable monitoring system that can be tailored to budget and need.

Conclusion

The integration of high-resolution satellite imagery, especially from PlanetScope, offers a valuable new toolset for land and water management in regional Australia. When combined with free resources like Sentinel-2 and Landsat, and supported by digital elevation models and drone data, this technology makes it possible to monitor water bodies, assess infrastructure needs, and support drought planning with greater accuracy and frequency than ever before.

These methods are increasingly accessible to graziers, regional planners, and environmental groups, and can complement existing monitoring programs. As climate pressures intensify, this approach represents a low-cost, scalable, and innovative solution for managing water, land, and ecological resilience in the rangelands of North-West Queensland and beyond.